I highly recommend Dani Bostick’s recent post at Sententiae Antiquae, ‘Classics for Everyone’ Must Be More Than a Slogan. Although directed specifically at materials disseminated by the American Classical League, it is an excellent entrée onto how the Classics are still used to make arguments about cultural superiority. Many classicists find such accusations ridiculous, but, as Bostick points out, because classicists are not offended by such arguments does not mean that they are not offensive, especially since Classics is an extremely white field.

Depressing yet necessary reading

An opinion piece by Herb Childress in the Chronicle of Higher Education from March 27 really hit home for me. It’s about how academics without tenure track positions are, often implicitly, regarded as failures, despite the fact that the job market is so atrociously bad that finding a job has as more in common with winning the lottery or being struck by lightning than it does with any merit-based process. Simply put, grad school conditions us to define success and failure in extremely specific ways, and to place the cause for that failure solely with the candidate.

I certainly blame myself for my inability to find permanent work. It is true that I blame other people too, but primarily I blame myself for the decisions I made about what I chose to study. I was hellbent on being an archaeologist, but because I was interested in Iran fieldwork was not really an option for me. I have always been trained in classics departments, yet I set out to study the Persians rather than the Greeks or Romans. I could justify this decision to myself: the study of the Achaemenids has never belonged to a single academic field, the skills necessary to studying material culture are transferable, I was studying under the doyenne of Achaemenid art, etc. But in hindsight these justifications seem meaningless and empty; all I can think of are the decisions I should have made that would (surely!) have gotten me a job by now.

But, honestly, even if I had different decisions, nothing would have changed. Early in grad school my adviser suggested I write a dissertation on Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, where the University of Michigan carried out excavations in the 1930s. It would have been perfect; it’s both Greek (Hellenistic/Seleucid) and Iranian (Parthian), it involves a archaeological excavation without necessarily have to spend years in the field in a politically unstable environment, and the site is chock full of coins, one of my favorite types of things. In my youthful stubbornness I rejected the idea. During the darkest days of my job search I would lay awake at night, wondering what would have happened if I had gone that route. Frankly I don’t think anything would have changed. I’ve mostly lost jobs to people working on mainstream Roman archaeology, and one or two people working on archaic and classical Greek (and at least one Aegean prehistorian, but I don’t begrudge her that!), not to Hellenistic Near Eastern archaeologists. And I wouldn’t have done all of the weird and interesting work I ended up doing, and carved out the (admittedly unprofitable) niche for myself that I now have on the academic landscape.

I don’t know the particulars of Herb Childress’ career. It’s quite possible that he too made some bad choices along the way. I also don’t agree with his facile discussion of what led to the current paucity of permanent academic employment. But I completely agree with him that the apparent ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of a given academic is the result of grad school conditioning, not merit. My view is that it is crucial to lay the blame where it belongs — on other people.

Book update

I am very pleased to report that my book Archaeology of Empire in Achaemenid Egypt is expected to be published in November, 2019!

Upcoming lecture at the Met

Next Friday I will be giving a talk at the Met Fellows Spring Colloquium session Bridging Eurasia. The talk is entitled “The Stepchild’s Stepchild: Displaying Ancient Iran in the Modern Museum,” and it reflects some of the challenges of presenting ancient Iranian art in museums. Admittedly it will be a rough, preliminary look at the topic, based on my own impressions and experiences rather than on a rigorous study of the subject.

The session takes place in the Bonnie J. Sacerdote Lecture Hall in the Uris Center for Education on the ground floor of the Met. The colloquium begins at 10:00, and my panel starts at 11:45.

Our article on the Getty’s Urartian belt

The study I have co-authored with Alexis Belis on the Urartian belt in the J. Paul Getty Museum and its relevance for the history of the ‘Parthian shot’ — both as a motif and as a military tactic — has been accepted for publication in the Getty Research Journal 12 (to be published in 2020). We are now finalizing the text and figures.

Upcoming lecture at UC Irvine

On March 11 I will be presenting at the second Payravi Conference on Ancient Iranian History at the University of California, Irvine’s Jordan Center for Persian Studies. The theme of the conference is “The Persian-Achaemenid Empire as a ‘World-System’: New Approaches & Contexts,” and my talk addresses the Achaemenid Empire and Africa. It will include discussion of tribute, diplomacy, ideology and the Red Sea canal, though I am still working out the details.

As I have noted here before I am moving away from the study of Egypt; accordingly, I expect this presentation, and any publication that may result from it, to be my last remarks on the subject for some time. That said, I have no idea where my career will take me next, and it is entirely possible that I will find it expedient or worthwhile to return to Egypt at some point. But now that my book is in press I am running out of things to say about it, while the allure of the Iranian Iron Age only grows stronger (I love a good beaked pitcher).

The first Festschrift?

In an editorial commemorating the first twenty volumes of the State Archives of Assyria Bulletin (vol. 20 [2013-14], pp. 1-31), the great Assyriologist Frederick Mario Fales observed (p. 6 n. 11) that the earliest Festschrift of which he was aware with content relevant to the field of Near Eastern studies is Orientalische Studien Theodor Nöldeke zum siebzigsten Geburtstag (2. März 1906) gewidmet von Freunden und Schülern und in ihrem Auftrag, edited by Carl Bezold (Gieszen: Verlag von Alfred Töpelmann, 1906).

Quite by chance I have come across an older example, from the United States in fact: Classical Studies in Honour of Henry Drisler (New York: Macmillan and Co., 1894). Although focused primarily on Greek and Latin, it also contains essays such as “References to Zoroaster in Syriac and Arabic Literature” by Richard J. H. Gottheil and “Herodotus vii. 61, or Ancient Persian Armour” by A. V. Williams Jackson.

This discovery has prompted me to be on the lookout for earlier examples, which I will post here as I encounter them. This project serves no scholarly purpose whatsoever, save to satisfy my own curiosity.

Incidentally, Fales’ entire editorial is very much worth reading (as is all of his scholarship) for its insights on how the field of Near Eastern studies has changed since 1987.

More on the events at the SCS

I’d like to draw attention to some written responses to the events of this past SCS, by Dan-el Padilla Peralta himself, Joseph Crawley Quinn, and the blog Medievalists of Color, all of whom have more intelligent things to say than I do. Needless to say, I’m not optimistic about the future of the field of Classics; actually, I think it’s long past time that it went away altogether, and that classicists had to account for themselves in departments of history, Romance languages, Near Eastern studies, etc. Until that happens I don’t expect we’ll move the needle any.

The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East

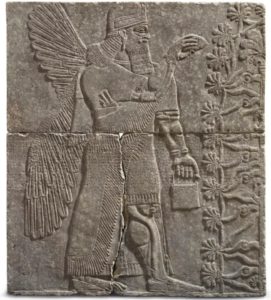

This morning the Agade mailing list delivered to my inbox the press release for the upcoming exhibition at the Met The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East, which opens March 18. The exhibition is curated by Michael Seymour and Blair Fowlkes-Childs (with whom I share an office). To wet your whistle, here’s the signature image for the exhibition:

I am excited by this exhibition for three major reasons (among a host of minor ones). First, it focuses on the material culture of the Near East (especially Mesopotamia and Levant) in the late first millennium BCE and early first millennium CE. This is not a period that gets much attention, in museums or in scholarly circles. For Near Eastern scholars this is when cuneiform finally dies out, and for Classicists it is mainly of geopolitical interest, specifically in reference to Rome’s wars with the Parthians and Sasanians or Silk Road trade. And the last time the Met gave much attention to this period was in 2000 as part of the exhibition The Year One: Art of the Ancient World East and West.

Second, the exhibition focuses on the agency of the people living in the Levant and Mesopotamia in this period, by examining how they constructed their various identities through art and material culture. Rather than thinking about them in terms of ‘Romanization’ (or its Persian equivalent, whatever that may be), it takes a local approach, considering each region on its own terms. In this respect it is very much of a piece with modern archaeological studies of borderlands, such as those pioneered by the late Bradley Parker.

Third, it explicitly addresses how current geopolitics have affected these regions. I am less familiar with this aspect of the exhibition, but I am looking forward to learning more about it when it opens in March!

Upcoming Met Perspectives talk about the Christie’s sale of an Assyrian relief

Next Friday (January 18) I will be giving a brief Met Perspectives gallery talk about Christie’s record-setting auction last October of a Neo-Assyrian relief, formerly at the Virginia Theological Seminary. It is part of a series of three gallery talks on ‘Art and Trade,’ and will take place at 6:00 in Gallery 401.