Despite the title of this post, I am not going to Syria next week (at least not physically). Instead I am going to Connecticut. I am attending the conference Dura-Europos: Past, Present, Future at the Yale University Art Gallery.

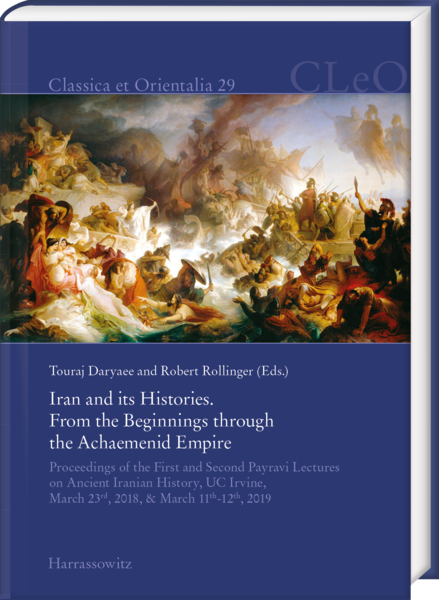

I’ll be giving a talk, growing out of my current research project on Mikhail Rostovtzeff, entitled “‘Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art’ (almost) a Hundred Years Later.” It’s a vague title to be sure (since when I provided the title I wasn’t yet sure what the talk would be about!), but I will focus on why Rostovtzeff’s essay ‘Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art’ is still important for the study of ancient Iranian art, even though the details of his argument have long since been superseded.

I am looking forward to the conference very much, but I am also intimidated by sharing a panel with Jaś Elsner! It’s like I’m George Thorogood opening for the Rolling Stones in 1981. Not that I mind in the least being George Thorogood; in fact, I like to drink ‘the George Thorogood:’ one bourbon, one scotch, and one beer.